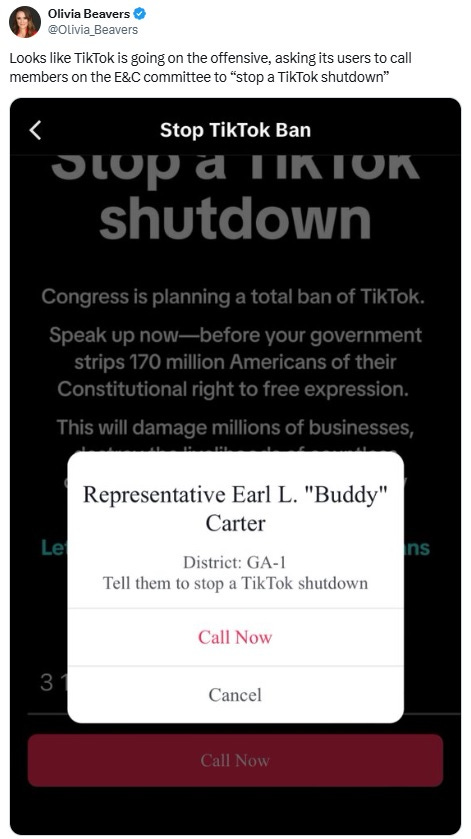

While it feels like ancient history now — in March of 2024, facing potential Congressional action over purported Chinese influence, TikTok sent a push notification to users across the United States:

The app prompted users to enter their zip code to identify their Member of Congress, then told them to call their representative in Congress to encourage them to vote against pending legislation, which TikTok characterized as a ban. Within hours, Congress was swamped with thousands of calls from concerned users. Members of the House Select Committee on the Strategic Competition Between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party slammed TikTok’s actions as launching a propaganda campaign against American youth, demonstrating the potential threat inherent in the app. Beltway journalists relayed stories of Member offices receiving death threats, threats of self-harm, and calls from young users who weren’t really sure what Congress was or why they were being asked to engage, and anonymous tips that the flood of user engagement had prompted some Members to shift to supporting the ban.

Prominent tech journalists Casey Newton and Kevin Roose, on their New York Times podcast Hard Fork, discussed the incident.

Casey Newton: But I just want to say, again, is the message from Congress that they don’t want to hear from their constituents about this? Is it like, only call us if you’re a registered lobbyist? Like, is that what they’re telling us? Because that kind of sucks!

Kevin Roose: Yeah, it kind of sucks, but it also is the case that these congressional offices are not set up to handle the volume of incoming calls that they got.

Casey Newton: Who cares?

Kevin Roose: I don’t know. You try getting 900 calls from angry teens. See how you like it.

Casey Newton: Why else do the phones exist in the offices of Congress if not to solicit constituent feedback? Is it like, oh, what, like your DoorDash order is at the front door? Is that the message that wasn’t getting through? I don’t understand this.

Kevin Roose: I don’t know. I think you should be able to text your congressperson. Because they text us so often when they’re fundraising or they’re trying to get elected. I think it would be turnabout is fair play.

Casey Newton: I agree with that.

There’s so much to unpack in just this snippet of a conversation, let alone the whole incident:

American civic wherewithal,

Public expectations of interactions with government (especially in the context of frictionless tech like DoorDash),

Deeply-held suspicions of new media in government,

The conflation of campaigns and “official-side” governing,

The civic shadow of exploitative and obnoxious campaign fundraising tactics,

The under-resourcing of Congress,

The role of media in shaping American civic imagination,

The power of tech and other companies to influence public opinion,

An increasingly punitive American public culture,

Intergenerational tensions,

The contested specter of foreign interference or deepfakery in American politics,

And so much more, each thread stranding into the thorny problem of constituent engagement in American government and civil society today — one that has only gotten more complex in the chaotic tug-of-war over the final bill and its divestment deadline in the presidential transition of power.

Good thing this is the first issue of a brand new newsletter to untangle it all.

Constituent/legislature contact — and welcome to Voice/Mail

Welcome to Voice/Mail! I’m Anne Meeker, and I’ll be your tour guide to the rich, strange, and surprisingly poignant landscape of interactions between constituents and their government. When not writing this newsletter (and even when I am, although some opinions expressed here are mine alone), I’m Deputy Director at the nonpartisan POPVOX Foundation, a nonprofit that works to help democratic governments keep pace with rapid changes in technology and society.

My colleague, Marci Harris, calls this set of interconnected challenges facing Congress the pacing problem, adapting a term from Gary Marchant. In Marci’s words:

The issues in Congress were not just a matter of an inability to keep up with tech in society; it runs deeper. It became clear that for Congress, there is not just one pacing problem, but three distinct and interconnected pacing problems: (1) the external — as Congress fails to keep pace with emerging innovations that are changing industries and society; (2) the inter-branch — as Congress lags the executive branch, compromising its ability to act as a co-equal branch of government; and (3) the internal — which results from Congress not employing modern practiced and technology for its own operations.

All three aspects of this pacing problem impact how Congress and the public interact with each other, but especially the third: how is Congress and modern democracy writ large equipped or not equipped to solicit, absorb, and act on public opinion? As the TikTok example shows us, this is a tangible, tactical question (what staff hours, tech platforms, switchboards, budgets are at a legislature’s disposal) that feeds into a values question — how do legislatures make people feel?

This question has been my jam for years, from my formative stint as a caseworker in a Congressional district office, to a year spent immersed in deliberative-democracy world, to the last year-plus I’ve spent talking to the people that carve and map out the landscape of constituent engagement today.

Thinking as generally as possible about how constituent engagement works in its simplest possible form, we can imagine the cycle as [input] => [output] => [result]. The emotional tenor of that result determines whether someone will reengage (creating a longer-term, more deliberative relationship), withdraw, find a new method of engagement, etc.

What TikTok offered its users was a new and easier method of engaging with Congress, and a reason to do so. In some ways, it was a glimpse of what public engagement with Congress could look like, from a constituent’s perspective: an immediate, almost-frictionless proactive invitation to people from all walks of life to participate, to share their experiences and insights on an emerging issue that was current before the legislature and not yet entirely captured by partisanship, seamlessly integrated into the ways millions of Americans already spent their time and experienced the world.

On the other side, Congress was clearly not equipped to handle this wave of constituent sentiment: it’s not comforting to see the world’s greatest legislature almost instantly overwhelmed, and sounding a bit peeved about the whole thing. And in the institution’s defense, this input was genuinely not usable for policymaking. Phones, mail, and email as the three current methods of at-scale interaction with constituents do not easily allow for identity proofing, they do not provide a representative sample of constituent views, and they rely on constituents to be the first mover. They can be spoofed, faked, or activated by a foreign adversary or a garden-variety advocacy organization. They’re hard to trust, and therefore easy to ignore.

The end result of this input/output mismatch is thousands of TikTok users feeling unheard — and crystallizing the feeling that Congress doesn’t want to hear from constituents. And returning to the interbranch pacing problem, the new Trump administration is happy to step into the void, making people feel heard by declining to enforce a law passed by Congress.

But if we actually look at how Congress spends its time, we see a different story. The institution has spent the last few decades investing in hearing from its constituents through channels where it controls the parameters of engagement. Half of Congressional Member-office staff are now located in state and district offices where their primary job functions are constituent-facing, in addition to more usually DC-based communications and digital staff. The “toolbox” for this work available to Congressional offices has exploded: in my conversations over the past year, I’ve counted almost forty separate tools and methods offices use to engage with their constituents today — many of which fly below the radar for most Congress-watchers because they are so heavily clustered in state and local offices or tailored to specifically reach segments of a district or state, and therefore mostly invisible in DC.

(And a heads up that we are going to talk so much more about all of these methods and what they tell us in this very newsletter!)

If investment signals values, then Congress’ investment in local and communications staff tells us that Congressional offices invest in interactions with constituents that are in-person (and less susceptible to interference), provide direct services (contrary to the perception of a do-nothing Legislative branch), and proactively attempt to break through the noise of the attention economy to reach people who may not be engaged (as opposed to passively receiving input).

The problem with these methods is scale. To take casework services (where Congressional offices work directly with constituents and federal agencies to resolve bureaucratic problems) as an example, a high-functioning House office can only handle around 500 cases at any given time, or around 2,000 cases per year, or 0.2% of that Member’s district. While these methods may be valuable to Congressional offices in narrow ways, they largely leave the field of play for public engagement at scale uncontested, and choked with campaign spam.

But the gap between these two extremes — casework vs. TikTok — is where the problem settles in and gets comfortable.

The TikTok example may seem relatively frivolous, but think about the bigger questions Congress and other legislative bodies will have to address in coming years, including regulating or mitigating the impacts of AI and AGI on the labor force, economy, privacy, legal system, corporate power, geopolitical competition, and more.

Where Congress is not equipped to proactively solicit actionable information from a majority of constituents, we have a problem. Where Congress cannot make constituents feel heard, appreciated, valued, and taken seriously as a part of the democratic process, we have a bigger problem.

The end state of the problem of constituent engagement, if left unchecked, is a loss of democratic legitimacy, a crystallization of public beliefs that government is either unaccountable to public will or too incompetent to carry it out.

So…whither public engagement? And what is this newsletter, anyway?

That’s a little dark. But I think the whole story has three points of hope, which are going to be the three main foci for this newsletter:

People do want to engage, they just want to be asked: despite Congress’ falling trust numbers, when given the opportunity and the invitation, the TikTok kerfuffle showed that thousands of people — yes, mostly young people, but all generations — would engage. And people around the country find new and creative ways to call on their government for the support and changes they need every day. Part of this newsletter will be documenting those instances of creative constituent-driven engagement — what’s showing up on government’s radar, and how is it getting there?

Congress and legislative bodies do value constituent engagement and input: In my conversations with Congressional staff in district offices and DC over the past year, I’ve identified almost forty separate methods and tools for engagement in common use by Congressional offices today — a more varied, creative, and dynamic landscape than you might imagine, especially for staff, researchers, and advocates who are primarily familiar with DC-based methods of engagement. A big part, probably the central part of this newsletter in the next few months, will be documenting how Congressional offices and other legislatures engage with constituents today, and thinking through what this engagement tells us about the modern role of Congress.

New technology changes what’s possible for engagement: Emerging technologies make new methods of engagement possible that collapse previous tradeoffs — for example, scale vs. depth, participatory vs. asynchronous, etc. To catch on, I think these tools and technologies have to make the case for their value to constituents and governments today, but we’ll talk about what that case might look like, grounded in the two points above. Mail is dead, let’s try some new stuff.

At the risk of sounding a little pretentious, as the late anthropologist David Graeber put it, the goal is —

To look at those who are creating viable alternatives, try to figure out what might be the larger implications of what they are (already) doing, and then offer those ideas back, not as prescriptions, but as contributions, possibilities — as gifts. […] Such a project would actually have to have two aspects, or moments if you like: one ethnographic, one utopian, suspended in a constant dialogue.

So that’s what we’re going to try to do around here, with notes from my research, interviews with people in this ecosystem, regular roundups of engagement-relevant news, and more.

I hope you’ll subscribe to join us for the ride, send me interesting examples of engagement that I might have missed, and talk to me about your own experiences engaging with government, and managing constituent engagement.