For many Congress-watchers, a map of constituent engagement might look like an island: you can see Capitol Hill, sticking up out of the water, with incoming streams of phone calls and mail and outgoing packets of letters, social media, teletown halls, and media hits. There’s got to be more out there — with half of Congressional Member office staff based in district and state offices — but the water is murky.

I don’t mean to subtweet anyone here; if you’re working for an effective and accountable First Branch against all headwinds, then you’re a friend. But in my last five years in more DC-focused spaces, I am consistently surprised by how little the work that happens in state or district Congressional offices is known or understood in DC — by Congressional staff, researchers, modernizers, and nonprofit/advocacy groups.1

I don’t think that we can have smart, productive, well-informed discussions about the future of constituent engagement or what’s working and not working without that grounding. So today, I’m going to share a high-level overview of our research from the last year on the full landscape of constituent engagement, including both district/state and DC-based methods. Like any good map, this one leaves out a lot of key features, but that simplification lets us focus on bringing other key landmarks into view.

Drawing a Map of Constituent Engagement

In my conversations over the last year with Congressional staff, support staff, advocates, journalists, and civic tech entrepreneurs, I identified forty separate methods for engagement in common use today, defining engagement as direct, unmediated contact between elected legislators and their constituents, no matter who initiates that contact.

To be included in our list, I had to hear from at least two Congressional offices that they were actively using or responding to this method.2 This is a living list that I’ll keep updated as I hear of new methods that meet the criteria above, and you can check out more in-depth descriptions of each engagement method at our Airtable. Any feedback on what I’ve missed is always welcome.

I’ve conceptually grouped these methods into six distinct but squishy modes of engagement that I’ll talk more about below. These are:

Responsive service, and

Let me also just caveat that this definition leaves out some elements affecting constituent/government interactions that are still important as context for official-side engagement — including, for a start:

campaign-initiated contact and voting,

media coverage of government,

Executive-branch engagement, and

third-party civil society engagement (e.g., a nonprofit commissions a poll and presents its findings to Congress).

Drawing a road map without topography lines doesn’t mean that the hills and valleys aren’t there — I’m going to come back to all four of these additional factors and how they shape the context for official-side engagement in future posts.

Direct Services

These are methods of engagement where the Congressional office is responsible for delivering a specific service to the community, mostly untethered to legislative outcomes. This mode requires offices to be service designers, developing public-facing processes that are consistent, reliable, and transparent to varying degrees. An interesting sub-bucket here is the proliferation of collaborative services where Congressional offices implement a program designed and facilitated by a separate entity (9 and 10). These “franchise” events are the subject of next week’s interview with Melissa Dargan, so stay tuned!

Many of these services are also expressive of Member priorities, like creative service events that can bring together tens of thousands of constituents. In fact, the House Chief Administrative Officer’s Coach program has just launched a database where Congressional district and outreach staff can share event ideas and templates — which also demonstrates the role of internal support organizations in promulgating “best practices” that shape how Members present themselves and what services they offer to their constituents.

Methods grouped into this category:

Casework/constituent services

Flag requests

Tour requests (not only for the Capitol building, but also other civic landmarks like the US Mint)

Inauguration tickets

Service fairs

Community Project Funding/Congressionally-Directed Spending (FKA earmarks)

Grants facilitation

Service academy nominations

Internships3

Convening and Coordinating

These are methods of engagement that bring together specific constituents around a particular area of local focus, and as such, will look very different between districts. For example, a coastal group may have a harbormasters’ roundtable; a rural community may have an agricultural advisory board; districts and states anywhere may schedule meetings with police chiefs, school superintendents, religious leaders, students/young people, and more.

In these engagements, the Member often serves as a focal point that can bring together multiple levels and branches of government around a goal or project — or, by attending another elected leader’s constituent event, they build good will that can be called in to help move a big project down the road.

12. Advisory boards

13. Attending other local electeds’ events

14. Task force standup or participation

Symbolic or Dignitary

These are types of ceremonial engagements where Members and staff play a witnessing (especially for 1:1 constituent meetings) and validating role, directing attention and marking symbolic importance. When the Member’s time is the most limited resource of a Congressional office, the decision to use it for a specific place, person, organization, or occasion confers its own kind of value. In some senses here, the Representative or their office is functioning as an “ambassador” from DC, with celebrity status and a megaphone that local constituents and groups can negotiate for.

15. Vietnam veteran pinning ceremonies

16. Award ceremonies

17. Certificates of commendation

18. Site visits

19. Availability to attend constituent events

20. Availability for 1:1 constituent meetings

Messaging and Branding

We covered these pieces last week with Dr. Russell, so I won’t go into too much detail here. Every single activity a Congressional office does comes back in one way or another to messaging and branding, so this category is a shadow behind every other, and can act as the force multiplier offices use to get the most leverage out of the higher-effort engagement methods like casework, town halls, etc. As one office I spoke with put it, the biggest challenge is “breaking through the noise” of everyday life to reach constituents directly; these methods make the attempt.

21. Weekly newsletter

22. Traditional press conferences

23. 499s

24. Print mailers, glossy paid front/backs

25. Billboards, gas stations, etc.

26. Texting programs

27. Social media

28. Radio ads

29. CTV, Hulu, YouTube, video ads

30. Programmatic ads

31. Paid social media advertising

32. Search engine ads

Responsive Service

When most people think of constituent engagement, this is probably the category they think of first — the vox populi of constituent sentiment that should be the animating force shaping how Members carry out their representational duties. As we discussed a few weeks ago, Member offices struggle to manage large waves of public engagement through these high-volume methods, including handling abusive and genuinely threatening behavior from constituents, disrupting the feedback loop that can make constituents feel truly heard when they engage through these methods. Not to tip my hand too much here, but I am most interested to see how Members and civic tech innovators find new ways to handle this type of broad public engagement.

We also can’t overlook the specter of AI in this category. In short, AI is not yet playing a role in increasing the volume offices handle through these methods, but it is affecting Member trust in constituent input, and their perceptions of whether constituents trust them.

33. Phones

34. Email/physical mail

35. Speaking with protestors

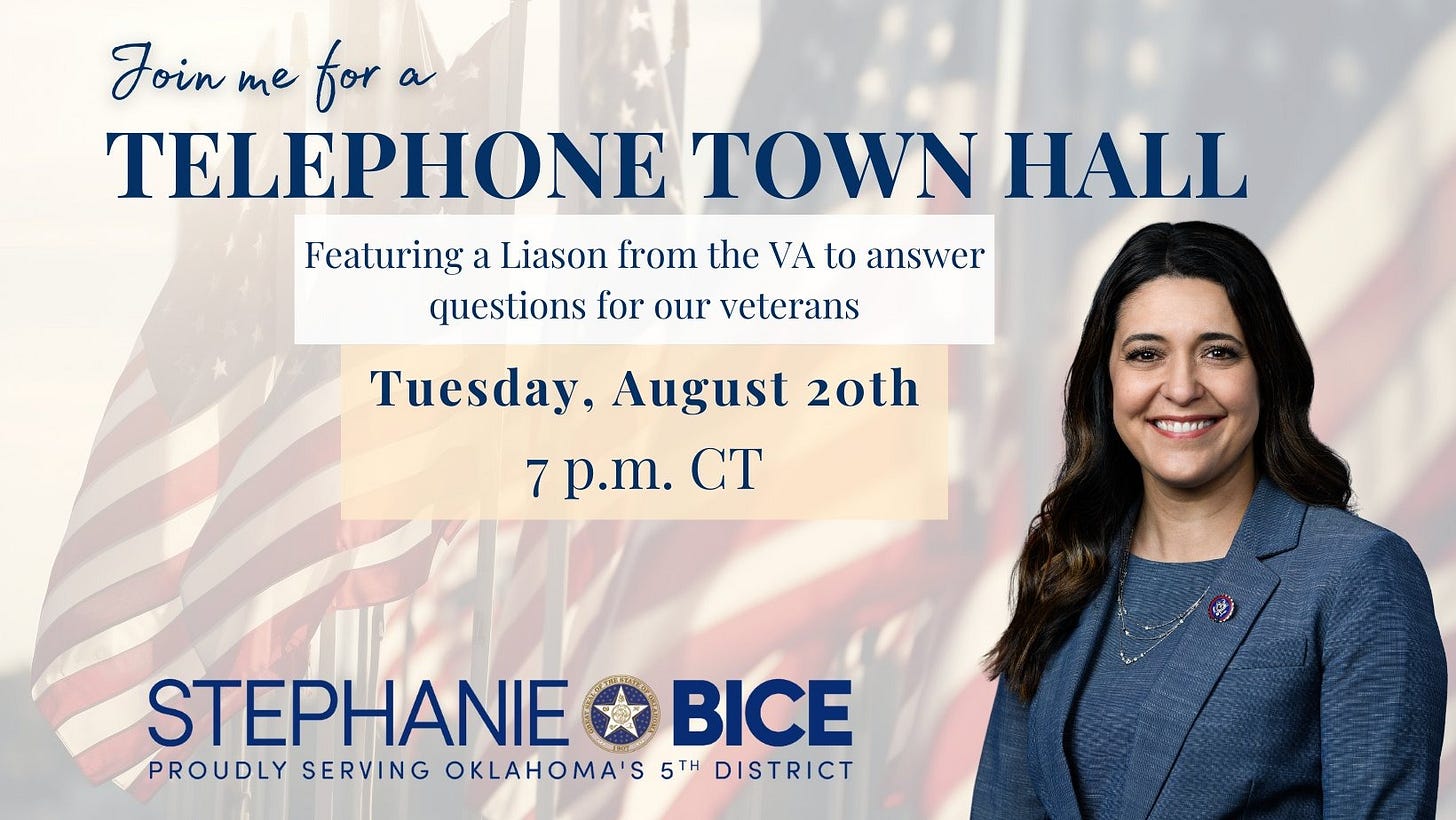

36. Town halls and teletown halls

37. Throw a party (less-structured, community-oriented events without a stated policy purpose)

38. Interest group meetings

Moving Legislation

Finally, these are the only two methods of engagement we found where the primary purpose was developing policy and/or building support/opposition for legislation or executive action. I suspect this is where we’ll see the most change in the next two years, with Democratic offices leaning into messaging and public demonstrations of opposition to Trump Administration actions. But I’m also hopeful that we may see new engagements pop up in the same vein as field hearings, finding new ways to leverage local expertise and connect it into policymaking.

38. Field hearings

40. Rallies

Three takeaways

Here’s what stands out from these methods:

Congress monitors and manages a huge number of channels for engagement, developed through accretion over time: If you were building a legislative system from scratch, you would probably have a narrower menu of methods of engagement, so that offices could really work to optimize specific methods. Instead, even the staff I spoke with were surprised as we walked down the list of engagement methods and they stepped back and realized how many separate channels they are responsible for monitoring and managing. Conversations about Congressional capacity should probably include the cognitive and attention-diluting load of this gamut.

Congress fills gaps: I am really struck by how many of these methods were framed explicitly as filling a need that is no longer met (or was never met) otherwise. Casework is the obvious example of filling in gaps in Executive-branch services, but communications as filling in the ways Americans no longer receive reliable nonpartisan news is another. Even some of the symbolic and dignitary work might have been accomplished by a religious figure or other community leader in previous generations.

Divide between constituent-facing and non-facing staff: I am sympathetic to and excited by the idea that AI and other tech might start to free up some of the repetitive labor of Congressional offices. But I do get cautious when people are excited that newly-freed capacity would go toward more constituent engagement: the hierarchy of a Congressional office is (mostly) more constituent-facing at the bottom and districts, and less toward the top and DC. It would take some norm shifting — and, likely some new methods of public engagement — to increase the amount of time more policy-oriented staffers are willing to spend talking to stakeholders and the public.

Check Your Voice/Mail

Last but not least! A short roundup of things that caught my eye this week around constituent engagement:

I am really paying attention to how federal agencies and other government entities are using X vs other methods for public service announcements.

Good window into the work it takes to bring an issue to Congress’ radar.

Why yes, we are still talking about TikTok, and how it has mobilized some relatively large-scale engagement (and some truly horrible violence) for Congress.

Frustration with current engagement methods does nudge people to run for office themselves — are we going to see a wave of newly-elected officials try new things?

We’ve all been there, buddy — getting engaged in local politics is tough.

Always great to see committees invite specific participation: the House Appropriations committee invites members of Tribes and Tribal Organizations to testify on American Indian/Alaska Native programs.

Lorelei Kelly writes about the tech underlying many of the engagement methods above.

At some point I’m going to talk about citizens’ assemblies, but for now, the New Yorker.

Excerpt from a new book about using citizen juries to moderate disputes on a Chinese ecommerce site.

What did I miss? Thanks for reading!

I am so excited to see people like Annelise Russell, Devin Judge-Lord, Megan Rickman-Blackwood, and others take steps to address this deficit in political science, and the Modernization Subcommittee of the Committee on House Administration and the previous Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress have all done great work here. That tide is turning, but we’ve got a ways to go.

Some of these categories are a little blurrier than others, but where there were grey areas, I’ve made back-end distinctions — if two tools/methods feel similar but they are supported by different staff roles on the Congressional office side, then they’re listed separately here.

Curious why internships are in this bucket, when they also benefit Congress? For Congress to legally accept unpaid or below-minimum wage support, the internship has to provide a service to their constituents. The service is a hands-on educational experience in the legislative process.