Customer vs. Constituent: A Conversation with Samantha McDonald

Why our approach to measuring constituent experience matters, and how to do it right

The last few years (decades?) have been boom times for the concept of “customer service” metrics for the federal government. Agencies increasingly have “CX” leads tasked with overseeing public interactions with agency programs and services,1 and the concept itself has been a tent pole for combining and coordinating various efforts to improve how government agencies work, and how they are able to solicit targeted public feedback to foster those improvements.

This is all great, and well-needed — but something about the “customer” framework has always felt a bit off to me. First of all, in a private company, management has the option to just change the product if customers do not like it — which is far from the case for the government, where agency activities and procedures are dictated by law (or suggested by law in a way that effectively is enforced as law, as Jennifer Pahlka has explained). Second, customer experience research in the private sector is about developing competitive advantage in a marketplace where the customer has choices — which also does not describe the landscape for most government services. There are no competitors for TSA or OPM.2

But third and most importantly, framing constituents as “customers” flattens the complex relationship between the people and their government — or rather “The People,” as in the source of power in a democracy. Constituents are not passive consumers — as in Jon Alexander’s wonderful framing. Maintaining the consent of the governed is more fundamentally, existentially important than a quarter’s profit-and-loss statement.

But while that nagging sense of discomfort is all well and good for someone who writes newsletters like me, what does it actually mean for governments who want (or are legally mandated) to figure out what the public thinks of their work? How can staff in elected offices and agencies actually solicit input from constituents in a way that makes sense for the unique context of government work, and respects all of those different multifaceted roles?

I’m so glad you asked.

One of the very first projects ever from POPVOX Foundation was the CivX Metrics Toolkit: a resource guide for governments on how to solicit constituent experience information. The guide was written by Samantha McDonald, a brilliant engineer and researcher fresh off of her PhD at UC Irvine. While it was published a few years ago, it feels more relevant than ever.

Sam recently returned from a “sea-bbatical” (you’ll hear more about that below!) and I was delighted to talk her into joining me for this conversation about the CivX toolkit, the difference between measuring customer experience and constituent experience, town halls, emerging technology for constituent engagement, and more.

Transcript

This transcript has been edited for clarity and may differ slightly from the audio recording.

Anne Meeker: Sam McDonald, welcome to Voice/Mail! This is a little bit of a reunion, since you were one of the first POPVOX Foundation fellows, way back in the day when we were still super new and even smaller than we are today. You really jumped in to lay a lot of the foundations for the work that we are still doing today on constituent engagement, the future of constituent engagement, all that good stuff. So it's really delightful to have you here. Would you mind just introducing yourself and a little bit about your background?

Sam McDonald: Yeah, absolutely. Thank you so much. My name is Sam McDonald. I received my PhD from UC Irvine way back in 2021 in digital democracy and the design of constituent communication. I actually got started studying Congress, civic technology, and digital democracy in general from talking to my sister who was an intern in one of the Senate offices.

I was telling her how excited I was about these new things that I saw online where if a nonprofit really wanted you to engage your Member of Congress, they would have these pre-filled emails. So it was already filled out. I could tell a Member of Congress how I felt and just send it on the way. And I thought it was great.

And I was talking to my sister about that when she was interning at the time. She said, "Oh, we don't read those," and my heart just broke. And I was like, "What do you mean you don't read those?" And it kind of became my mission throughout my PhD to really answer that question and understand why this is happening. What's going on?

And it goes so much deeper than I originally thought from that whole experience. When you really dig into it and ask the staffers, they say, "Oh yeah, I get a thousand emails a day, they all look exactly the same. I can't tell if a robot wrote it or not." And you realize, oh, there's something here that needs to be explored.

So my background is really studying those questions of how technology is designed in Congress, how we can design technology in different ways to promote ideas of representation and constituent engagement, and really be innovative in that space. And that's why I got the opportunity during my PhD program to work with POPVOX and really collaborate on an innovative solution as part of my dissertation.

Anne Meeker: And then one of those big projects with POPVOX Foundation, again, early in our history, was the creation of the CivX Metrics Toolkit, that presents starting points for evaluation metrics for governments that are not strictly based on customer experience. And you put it so beautifully in the project itself — I just went back over and reread the whole thing recently, and I refer to it all the time, it's still so good. So I'm just going to read from what you wrote here for a second:

"A CivX approach views people not simply as customers who need to be satisfied within the context of a single interaction or service, but as contributors with power and agency over institutions that affect their everyday lives and the lives of others within their communities. The civics approach invites agencies to consider interactions between individuals and government not in isolation, but as part of a larger experience of the individual in one of their many roles as constituent, customer or partner, citizen and more."

Which I love so much and, again, refer to it all the time.

So tell me about the genesis of this project. You've given a little bit of the background, but what was the need for it? And who did you have in mind to read this when you were working on it?

Sam McDonald: Yeah. So this project and this toolkit really came out of doing an experiment with Congress. After I did quite a few years of work to understand what's going on in Congress, how do Members of Congress think about constituent engagement, what sort of tools do they use, how are staffers involved in this process, and how do they think about it — it really became clear to me that there was opportunity to work on something better and more innovative than the current status quo of how people communicate with Congress.

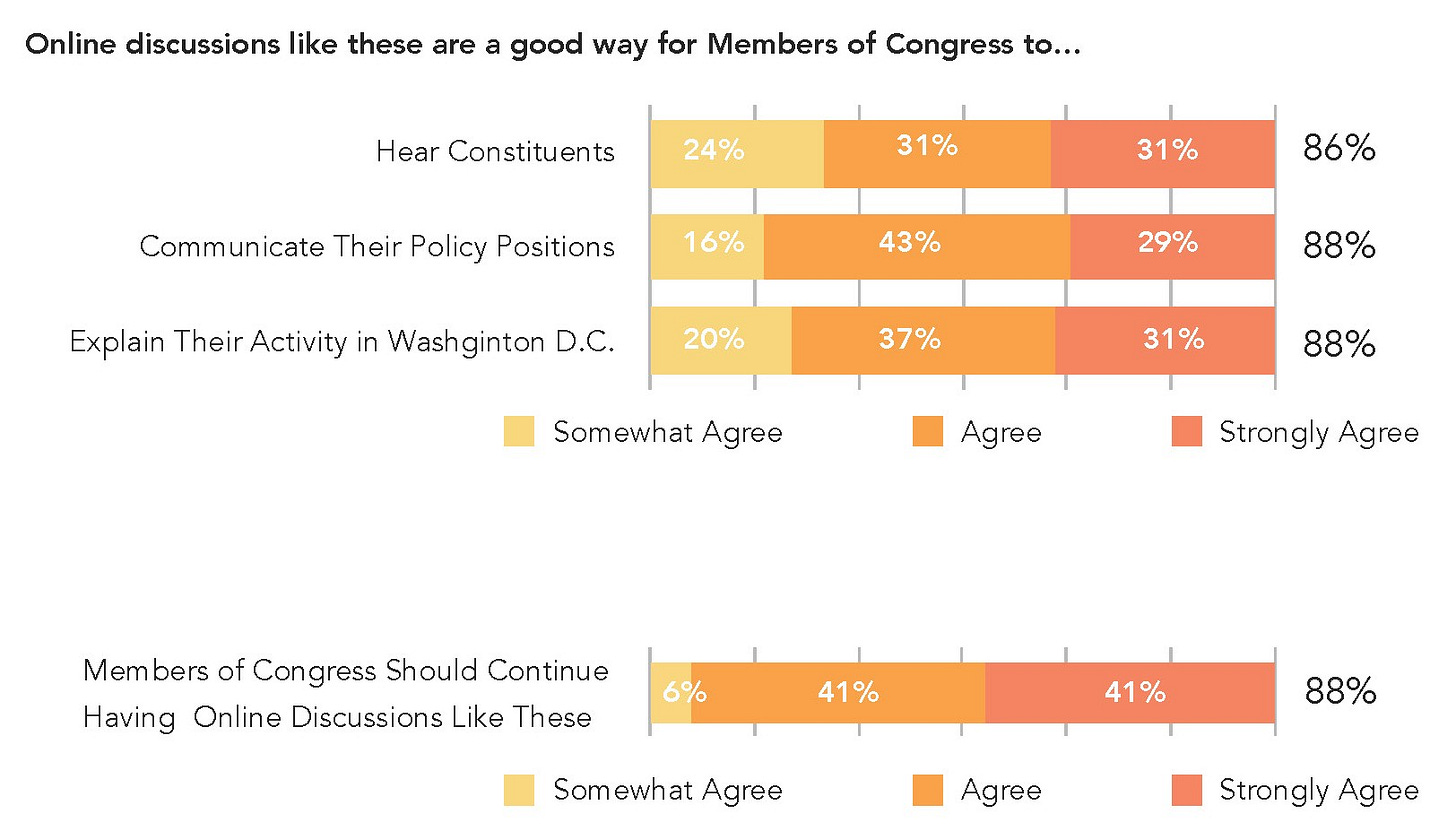

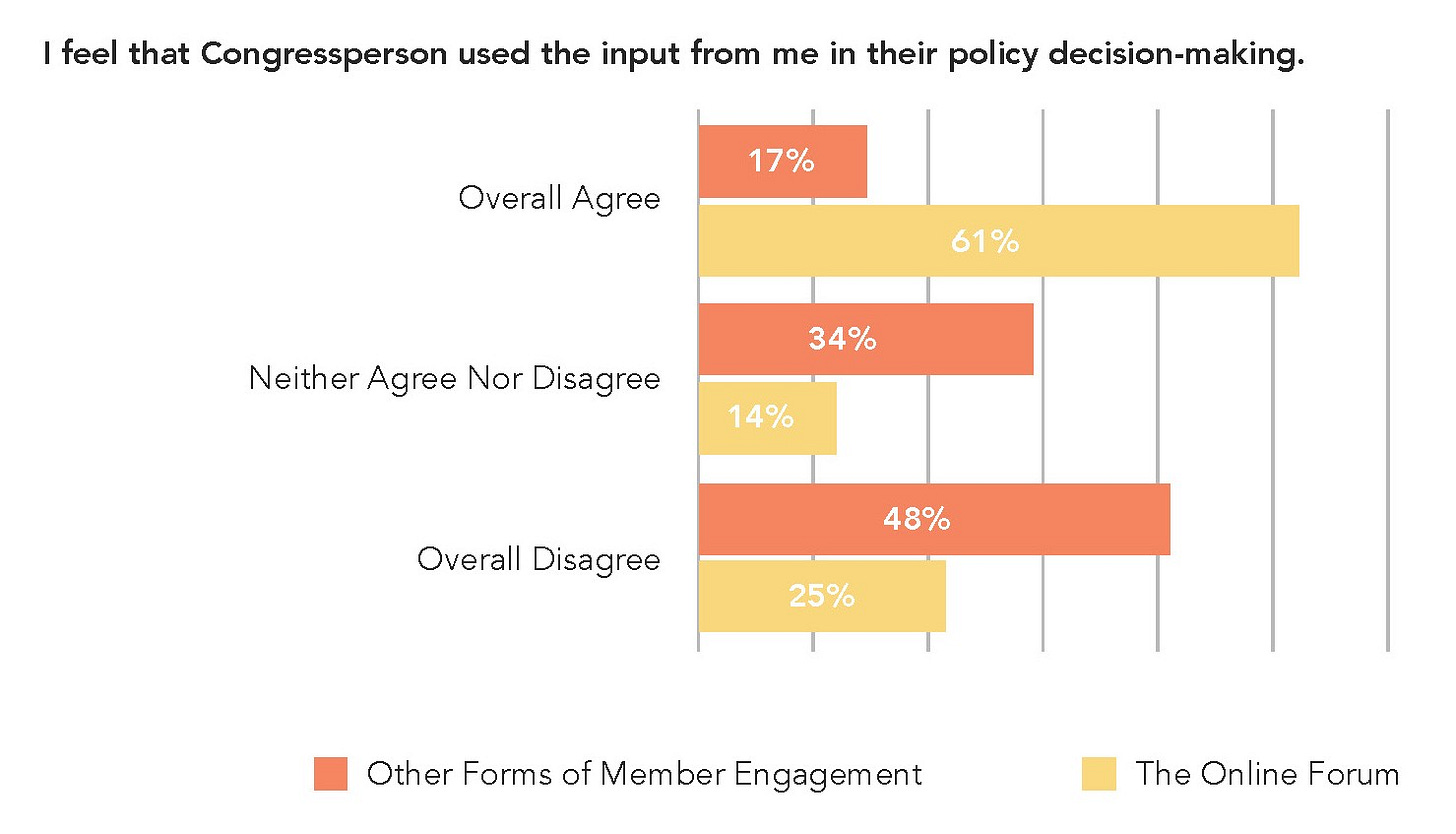

So working with POPVOX and the amazing LegiDash software, we came up with the idea of running an online, week-long, single-topic forum for deliberation, sort of changing the status quo of how people have town halls and how people communicate. Saying, “hey, let's invite a random representative sample of constituents to come and have a dialogue with their Member of Congress online, and do it so that it's asynchronous so people can log on and off whenever they're available to make it more accessible, and have information provided to users before they attended so we all come from a baseline of knowledge and participation.” And let’s really see, does that change the way that people think about their Member of Congress? Think about engagement? Does it make for better discussion and better contact and dialogue? Does it keep the Member and the staffer informed in a different way? Does it make them take different policy actions or think about topics differently?

So that was really the essence of the experiment. And it really showed an amazing contribution to how we think about civic metrics, because so much of the experiment required measuring different aspects of what people think about this experiment. Did they like it? Did they not? Was it accessible? Was the platform usable? What did the Member of Congress think? So there were so many different things that you had to think about to measure in this experience. And that's where this toolkit came from — what sort of metrics did we find were the most appropriate to measure experiences like this, and to think about what it means not only for customer experience and those questions, but civic experience and democracy and how we think about representation and things on a bigger scale?

So that experiment was what really led to designing these metrics and then putting them in a toolkit for the greater public to use in different contexts.

Anne Meeker: Love that. And then that contrast between — as you say — that really big picture scale of democracy, and seeing this person's experience with government in that full context — versus this kind of smaller scale of just that one single interaction, is really interesting. And I think customer service metrics have really found their way into government a lot in the last few years. So it seems like this project was meant in part to kind of push back on that overreliance on those customer service metrics. Do you have a sense for where those smaller scale, traditional CX metrics can steer government services in the wrong direction?

Sam McDonald: Yeah. So I think customer experience is going to be always a very important part of any sort of relationship. But when we start thinking about citizens as customers that need to be satisfied, we're not really looking at what is the point of representation and how that relationship exists. And that's why I think there's such a disconnect where people are reaching for satisfaction. You know, you’re not always going to satisfy your entire constituency that you're representing. Way too many people have way too different ideas and opinions. So I don't think those metrics are going to lead exactly to good ways to measure how they're doing as a representative, but also looking at how people can engage and just have more quality conversation and influence the Member and their decisions.

So trying to figure out different ways to measure civic experience on top of things like customer experience, I think are just really good ways to get a more holistic approach. So questions like, do they feel seen? Do constituents feel heard? Do their actions lead to reactions from officials? Could this cause constituents to take other forms of civic action or engagement with the Member in different ways, or even volunteering or things related to other parts of that question?

So I think there's just so much more opportunity to go beyond customer experience and really dig into, well, why are we all doing this in the first place? And I feel like those questions that are really around satisfaction, which is really the heart and soul of a lot of the customer stuff, really misses the main point of these engagements.

And knowing that not everyone's going to be satisfied, we can sort of have a bigger sense of democratic inclusion and democratic engagement that will leave people fulfilled in a way that isn't just, "Thank you for responding to my letter," or "Thank you for having a town hall in the first place." We can go beyond that.

Anne Meeker: And I'm so glad you brought up town halls, because these have been clearly the subject of so much…angst? Sturm und drang? in Congress recently. And I keep thinking about town halls really as kind of a critical example here of that tension between how you want everybody attending an event to feel happy, but that's not the purpose of what this engagement is supposed to be.

So can I ask you to just think through town halls as an example? If a Member of Congress came up to you right now and said, "Sam, your toolkit is wonderful and helpful. I am struggling to figure out what to do about these town halls. I would love to think of a different way to do this…” Where would you start to help them use this toolkit to figure out a better way to do this?

Sam McDonald: Yeah, it's a great question. I mean, I think it's important first to step back and realize that — and people are going to get maybe uncomfortable when I say this in public — Members of Congress do not have to listen to their constituents once they're elected. It's horrible to say. It doesn't mean that they shouldn't do it — they absolutely should. But there are no legal mechanisms that keep them accountable in that responsiveness aspect. That’s compared to something like the EPA, where if there's a regulation that's being considered, they have to read the public comments. That's completely different when it comes to Congress. So in some ways it's a little bit uncomfortable, but in other ways, it's a good way for the Member of Congress to step in and say, well, what do I want out of this engagement?

I don't think Members of Congress oftentimes know that they can really set the expectations for what they need for their office to be effective in lots of different ways that aren’t always the status quo. So I think starting from there and asking, well, what do you want to get out of your town hall? What are the things that you think are important to address? What could help your office? Maybe when it comes to listening to the constituency, is it a single topic that you are still sort of unsure of and want to hear from the public? Is it a specific group of people that you want to listen to? These are all different things that I think if Members of Congress and their staff start thinking about how can we help serve our needs and sort of construct a town hall in a way that works. I think that would be really great.

Now, obviously there need to be spaces for people to feel seen and heard. So we also need to look at that as well. But I think first, stepping outside that box and looking at all these different ways to make and design a town hall, I think will lead to some interesting ideas. And then kind of what you're alluding to too, is like, once we're doing those town halls, how do we measure people's engagement? Engagement can come in a lot of different ways, and not just "Are you satisfied?" because town halls are contentious. People are never going to be satisfied. And part of the purpose of those town halls is for people to speak up when they're angry or upset. And that's sort of a method to do so that we've invited people to come into.

So being able to ask questions and be able to make metrics for people to feel like — when are they comfortable speaking up? Is it an uncomfortable space? Are there different ways that we can allow people to speak up in these town halls or different methods? Are people feeling that the town hall is accessible at the right time or the right place, or do we need to have multiple or try them in different locations? I feel like there's so many different questions that can be asked. And I think the toolkit does a great job of setting that up for anyone who wants to look at it to help address their issues with town halls, just going through and looking at those questions that we asked in the toolkit around like, well, how are you recruiting and identifying people to show up? Or who's actually showing up and maybe who are you missing from your constituency? What sort of knowledge are people providing? That one's really hard. I feel like civic knowledge and having people come to a town hall with everyone having a baseline knowledge of what's being discussed is a very difficult thing to achieve. But it's something that you should constantly strive for. So also thinking about, should Members of Congress be the knowledge providers, provide experts, provide information and inform the public as part of their town halls about situations?

So there's lots of different parts of that toolkit. Also things like measuring people's trust and feeling comfort in that situation, being there. There's just so much to explore. So really starting with that toolkit, I think going through those questions and then asking the bigger picture of what do you want out of this town hall is a great place to start.

Anne Meeker: That's really fascinating. So it sounds like a little bit of maybe the intent behind the toolkit then is to help Members and other elected officials, to your point, where legally permissible, think about how to solicit and when to solicit constituent engagement, but to really kind of go beyond, "Well, this is the tradition, and this is the norm for how we engage constituents, and so we just have to find a better way of doing the thing that our constituents expect.” It takes a little bit of risk and takes a little bit of courage for Members to kind of break with that pack and say, “you know, of course every other Member does a town hall, but maybe I'm going to think about doing something different here.”

Am I on the right track with what you're hoping that this kind of maybe nudges some legislators to do?

Sam McDonald: Yeah, absolutely. And that's why, for my dissertation, everything is private for identity, but having one Member of Congress say, "Yeah, I'll experiment with something different. Let's have an online week-long town hall. Let's invite people, and let's run it through a university graduate student" — like, that took a lot of risk to put that trust into someone, into these institutions.

But I feel like those experiments are what caused the most meaningful interactions and the most progress towards thinking about different ways to get more citizens involved in this process and having more stake in this process — and also the Member of Congress being able to hear from more people. I mean, when people show up to town halls, it's always the people that are the most engaged or the most fired up about a certain topic, which is amazing. But there's a lot of people in the district that they don't get a chance to talk to, maybe can't show up to a town hall or don't have the capacity to do that. So finding ways, legally, to be able to reach out to those people and experiment in different forms, I think is just a great opportunity for innovation and something that we just haven't seen much yet, especially in the US. I think a lot of other places are starting to do this in different ways, but we just haven't gotten there yet, at least on the Congressional level.

Anne Meeker: Definitely. And so part of that is, like we said, it's a risk on the part of the Member of Congress. And then it's also asking a little bit more of — possibly asking a little bit more of the constituent participating, saying "Hey, maybe you've been used to going to a town hall. You've been one of those loudest, fired up people in the room, but now you're being asked to do something different.” And one thing I really love from your toolkit is how you acknowledge that one difference between CX and CivX is taking the long approach to how people have cumulative interactions with government, so all of your previous interactions with government shape all of your expectations for what's going forward. How does that work?

Sam McDonald: Yeah. So especially when you're looking at things like — one of the measurements that we suggest in the toolkit is efficacy, specifically internal and external political efficacy. These are sort of big concepts in political science, but essentially they point to whether or not people feel like they can participate in civic engagement in conversations, and then whether or not those engagements are responsive to them and they feel like they're being listened to and all sorts of aspects of that.

But those measurements do not just happen from one intervention, one town hall, one Member of Congress call — those sort of build up over time, and people's confidence and ability to engage and understand the system build up over time. So that's why I think those measurements are so important, but they take so many different interactions into account to get to that bigger picture of involvement.

So I think being able to measure those things over time is really important. And that's why it kind of goes beyond customer satisfaction, too, because it takes into account so many more aspects of the overall experience that they're part of.

Anne Meeker: Definitely. And one piece of that efficacy that, again, you also land on in this toolkit is this idea of civic wayfinding. So just how do you figure out which part of the government you should be talking to and how to find them? And I will say, talking to folks in Congressional offices, state offices everywhere, a huge complaint I get — not even a complaint, but a huge factor in their day — is helping people find the right place when they reach out to the wrong place.

So I think this is kind of an underappreciated challenge for folks in elected office. And trying to work on constituent input is just, hey, a lot of your time is just spent giving them a different phone number. So you include wayfinding as a way to measure whether people come away from an engagement more informed about just where they are. So can you just walk me through how does that work?

Sam McDonald: Yeah. So I think the section of the toolkit that's on wayfinding works with a lot of different aspects of not only how accessible it is to discover these spaces, but then once they get there, do they know where they are in the context? There's a lot of assumptions that come when you even get to a town hall — like, do you know who the Member of Congress is? Is this a Member of Congress or is it a Senator? Maybe some people just don't know how that works. And it's just such a complicated and large system, that starting with the baseline expectation of: how are people discovering these conversations and knowing where they are? Even things like, "Hey, we're talking about a bill specifically — where is that bill in the process?" Okay, for the information for the public, "When the bill gets here, then it goes into this next chamber." Like there's so many of these little things that can help people locate where they are, not only in the process of discovering this information, but also the process that goes on in that engagement. I feel like there's a lot of opportunities for that sort of wayfinding of helping people in navigating through that.

And even — I called a Member of Congress the other day about a specific issue. They couldn't answer the phones, but they were already ready to go with the voicemail recorded: "If you're calling about X, this is where you go or this is what's happening." And the fact that they already had the forethought in that process, I think those are sort of wayfinding aspects that we're describing. It's like that could be a great part of just user experience, really. Does that point to aspects of customer experience? But this bigger level of people's engagement and feeling like they know where they are in the process and can engage.

Anne Meeker: Definitely. And I think maybe that starts to point at a new model or a new approach to civics education — we always think about civics as like this thing that you should do in high school, where you do the Schoolhouse Rock stuff, and then you come away as a fully-formed citizen and like, you're ready to go. But government doesn't work exactly the same way it did when I was in high school (And I wasn't in high school that long ago, for the record!). But you point to how every interaction with government has the potential to be an opportunity for ongoing civic education. You might come away from that interaction knowing a little bit more about how to do this next time, or what your Member does or what's the legislative process. There feels like a lot of potential there.

Sam McDonald: Yeah, absolutely. And like to your point, it's sort of embarrassing to say, but I didn't really know what Social Security was until I got to college, because I think there was an expectation from parents that you learned in school, and then school expected that you learn from parents. Or like how to do your taxes. There's just so much information that gets missed when we make these assumptions even on just like, representative level or any public official, and we're going to start with the wrong set of expectations.

So that I think is super big, even as a first step just to be like, okay, how do we make sure everyone's on the same baseline of knowing where they are and how to navigate this whole messy process?

Anne Meeker: I really love that. And then one other metric in the toolkit that I really keep thinking about is that you talk about trust a lot, and one of the steps is thinking about trust and how to measure trust. And this feels like one of those metrics that maybe bridges kind of traditional CX and CivX a little bit, in that a lot of customer experience questions really do have something about trust. But you say in the civics toolkit that trust is a metric that should be deployed with a little bit of caution. So why is trust hard to measure?

Sam McDonald: Yeah. So at least from what we know from the academic findings, if you ask people if they trust their government — or if you don't get more specific on specific government institutions or groups or whatever they're in — there's almost always a correlation between what they think about the situation and the current president or Congressional situation. So that's why I say take trust with a grain of salt, because if you ask people, "Do you trust your government?" even if it's the state government or the local government, they're going to tie that, at least unconsciously, to what's going on in the broader media, what's going on at the highest level of government.

So that's where trust is really hard. I mean, having any sort of question be measured statistically and be able to get those constructs right is always very challenging. But trust in particular comes from such a deeper sense of so many environmental factors that when you're asking that question. I think it's still a really important one to answer, but kind of diving in and getting more of the qualitative metrics of where that trust is coming from, and having people explain their answer — like, "Okay, you think trust is this number or you strongly agree, explain why that is” — gets to that quality. That, I think, would also build up a better metric for trust in that way.

And again, I think it's a really great question to dive into, but I do think it leads to a lot of caveats, a lot of assumptions. And we don't always get that qualitative aspect to it.

Anne Meeker: And that feels like it comes back again to what we were talking about with the cumulative impact of a long-term set of experiences, too — that if I got jerked around by the DMV, I'm going to come into my experience with my Member of Congress maybe a little bit more hyped.

Sam McDonald: Yeah, 100%. Especially when you get moved around with so many different agencies and people — it all gets connected.

Anne Meeker: Definitely. And so then one other really unique and fascinating angle to your background and what you brought to doing this toolkit is that you combine tech and UX design with a really deep academic experience of political participation, all that good stuff. So you write in the report that:

“Research from the Center for Public Impact found that many people feel government interactions are characterized by a lack of humanity and a lack of empathy or authentic engagement. Humanizing these interactions, even by demonstrating that real people are behind government processes, can strengthen social cohesion and improve the perceived legitimacy of governing institutions."

In our earlier conversation, when you were talking about just how the cycle of responsiveness on constituent emails works — you're right, you can't tell if a lot of these letters were written by robots. But then that also gets to a lot of the skepticism I hear from Congressional offices about using new tools, using new technology to interact with their constituents too: they think that relying on tech tools to mediate that engagement would harm the progress, any progress that they've made on humanizing these interactions. Do you have thoughts for offices on just how do we mitigate that tension between humanizing these interactions, knowing that that produces a better outcome, and also just needing to get through the volume?

Sam McDonald: Yeah. And I think like, kind of like you alluded to, new tools, especially things like AI tools and things like that do offer great opportunities. But it's about parsing out how we're going to go forward. So coming from a tech background, technology is the same as government in my opinion: It has the potential to do incredible good for the world. It has the potential to do incredible harms, depending on how it's structured and what happens. It's always both good and bad, and I don't think we can ever escape that duality. And the same thing comes with every tool that's going to be used in Congress when introducing new technologies. So we can take tools like these artificial intelligence and machine learning tools, I think they can be super helpful. I don't think that anyone wants to talk to a robot, especially when they already feel distant from their government. So maybe those methodologies should be avoided, especially if we find out that tools are being used for formatting language or the way that they're responding. So that's a little bit difficult.

But that doesn't mean that those tools can't be useful in other ways. I mean, you know, as caseworkers — wow, would it be amazing to have tools that can help triage casework and see what is the most important, how to navigate that and how to get through it so people are addressed quickly. Or there's a lot of Members of Congress that represent a lot of people where English is not their primary language. Can AI make it rapidly faster to translate in real time and have conversations with constituents who have language barriers? Or with the bombardment of phone calls, emails, faxes, letters, finding signal in that noise and being able to do it in a way that relieves a lot of staff burden so they can get to that bigger picture and then use their superpowers in other places that can be more impactful?

So I think there's a lot of opportunity for those tools to help staffers throughout all these different processes. But as long as they're done ethically and with transparency, review, and making sure — even having feedback from their own constituents and being like, "Hey, I'm introducing these tools. What do you guys think?" Just asking people for their feedback oftentimes increases their comfort level and sort of sense of exposure and experience.

Anne Meeker: Interesting. I would just a flag a previous post in this series — we recently had a wonderful case study from my former fellow Nick Dokoozlian, who shared his learnings about potential adoption of AI tools at the county level in California. And that's something that he really pointed to in his conversations with political staffers, was that you really need to do so much explaining, and you need to give people so much opportunity to weigh in. The transparency of like, "Hey, this is what I'm doing and why" is really critical.

Sam McDonald: Yeah. And it's — and I understand how hard it can be. I mean, you know, first and foremost, staff are so much of the superpower of Members of Congress. It is a tiny little organization that just runs. I don't even know how people have the energy to manage everything in a Congressional office. But staff do so much. And having any little bit more support to make their jobs easier is just going to make everything work much more effectively. So like, I definitely see incredible opportunities. But yeah, absolutely. Taking those things generally and with a really civic focus and open mindset are super important.

Anne Meeker: Definitely. And I think we're starting to pull on a thread here that I think is really interesting about the role — specifically legislative offices like Members of Congress as offices — like the role of staff. So we've talked a lot about trying to humanize these interactions. But at the same time, you know, staff work for the Member who has the ultimate decision making responsibility — like they're the ones whose names are on the ballot, to use a cliché.

But at the same time, you do point out that staff really take the burden in a lot of these interactions, especially ones that are — you know, we've talked about in this newsletter — interactions where constituents are just looking for an emotional outlet. You're angry and your Member of Congress is there, and they're responsible in some way.

So I'm curious just how you think about that tension: that the staff are really important, but they're also submerged and they're taking on the burden while they're doing the work. Where do we start?

Sam McDonald: It's such an important question. And I've always asked myself, what would it look like if staff had the opportunity to be more transparent about them speaking? Not that they're speaking on behalf of a Member, but it's them on the other side of the communication, in whatever form it is. Staff have so much information, and sometimes even legislative staffers have so much more of the nuance of laws going on, because Members of Congress are dealing with so much at once, but their staff are really diving into a lot more specific things. I oftentimes feel like if constituents were able to communicate more with staff, they would not necessarily be influencing the Member more, but they would get more knowledge, more insight, and actually more of a holistic chance — like the ability to influence how the whole Congressional office is working in a lot of ways.

And it's so interesting from the technology design perspective, because one of the things that I've thought about, especially with the experiment we did with Congress, is when we designed the experiment, it was a Member of Congress talking online with their constituents. But I don't think we ever thought about designing staff accounts so the staff could engage as well with their name on it, saying, "Hey, I'm Staffer so-and-so. I focus on this area. This is why I'm putting input into this conversation." There's just so much knowledge there that I feel like staff — not that they're necessarily underappreciated before, but being able to let them show up and be part of that conversation. I just feel like it not only does it humanize the conversation more, and so you know who you're talking to when you call a Member of Congress and you pick up the phone.

But just for [constituents] knowing that there's a human being that has expertise, that does so much for the Member, that can be part of the engagement — I think it would be interesting if we saw that more. And right now a lot of technology designs don't allow for that. Like it's always a Member of Congress-facing thing.

And maybe if it is a recess, just like anything and all these other things we've been talking about with town halls and things for Members of Congress to redesign, but having your staff take sort of a frontal approach to a lot of this communication. It may actually be better, even though it feels like a really risky thing to do.

Anne Meeker: I love that. So something I've observed among a lot of us, kind of Congressional modernizers, pro-democracy researchers, advocates, is that sometimes — I'm using myself as an example here — we almost in some ways stop seeing ourselves as participants in the system. We feel like we stand a little bit outside of it. We study it, we talk about it, but I am not what you might call a super engaged citizen, I am a little bit embarrassed to admit.

But you've spent the last few years actually on a sailing sabbatical, which is the coolest thing in the world. And then by necessity, ended up spending part of that time really deeply involved in your local and state government. So can you tell us what that was like? And then how has it changed your perspective on civic engagement?

Sam McDonald: Yeah, absolutely. So yes, I have spent the past two years on a “sea-bbatical.” My partner and I had a dream of buying this little thirty-seven-foot sailboat and sailing around the South Pacific and Mexico and California. And we did it because you have to do those things when you're young and just sort of go for it, and we don't regret it.

But part of that process — I won't dive into much in the details because then we'll be here for hours, but essentially, there was a big push in our local government that we believed was going to be detrimental to the safety, the affordability, and the accessibility of tidelands and oceans in California. And it has taken an army to get where we are, and a ton of unpaid labor from dedicated individuals that really care deeply about maritime culture, to sort of push back against a lot of the different things that we've seen pop up from different local agendas.

I don't think that necessarily this whole experience changed my perspective on citizen engagement, but it definitely cemented two truths in my mind that I think are really important.

Number one is that accountability is key in everything here. A government entity can create as many town halls, as many engagement events, as many Q&As and listening committees and walking chats and public letters as they want. But if they're not regulated, or have formal structures that keep those governments accountable to make change based on public input, or respond to it and explain why they are opposed — then a lot of that communication can be perceived as meaningless. And that's always my biggest fear with any form of government engagement, that if we create more and more ways for public officials to reach out to their constituencies, some will take advantage of that and say these systems are approved later on. Like, "Look, I responded to you. I was part of that process," even though they had no evidence whatsoever of that information going towards anything meaningful. So accountability is so important in that, because from our own experiences, so much of that engagement, is just really hard to see without that proper communication. And honestly, even just saying, "Look, I disagree and this is why" — I think that as a baseline is really important. And that was cemented from the projects I did, but really cemented by some of this local advocacy that we're doing.

And then the second one that I think really was cemented was that technology does create amazing opportunities for accessibility. There's one state commission in particular now that's just a fantastic example of government trying to make things more accessible. California is a huge state, and this one commission would literally travel to different parts of the state every single month to make sure that anyone who would attend a commission meeting could be there, and they are constantly moving from place to place to make it more accessible physically. But then they also hired an amazing team of technology recorders that broadcast the meeting, that control the zoom for the meeting, that control sign-ups, that have all this wonderful equipment so they can zoom in to each person's face, and microphones are always working perfectly. Like it was like six or seven people, and I met them personally. They travel around in the van following this commission to make sure that the technology works flawlessly. And it does. And it's really impressive when it comes to the accessibility and being able to engage in that way.

This is in contrast to a more local commission that we're also dealing with that, despite being a very wealthy city, claims to not be able to record meetings, and we have to show up every week with a high school student that we pay to record the commission meeting on a cell phone and publish it on YouTube. So, the contrast was there of how accessible and inaccessible these commissions are.

But to see one commission go above and beyond and see how possible that is to get people involved and still be part of that discussion, no matter where you were in the state, was truly amazing, and really showed the capability of technology to sort of help people be more and more part of these processes when they couldn't before if that commission was just stuck in like Sacramento, where most of those commissions are.

Anne Meeker: I am low-key obsessed with the idea of just roadies for government. Like, that's so cool.

Sam McDonald: Yeah, they're pretty nice. The guy who’s been paid to do that, like, literally is just designing his van so he can move around with them. It's amazing.

Anne Meeker: Oh my gosh, I'm obsessed. And that's such a creative use of time and resources. I can't imagine the process it took to get that approved. But if it works for one state, that seems like no reason it couldn't work for other activities.

Sam McDonald: Yeah. No, absolutely. And it was just incredible to see. And it's always funny going to these meetings from the flip side and being like, I'm a constituent in this situation. How do I feel about this engagement? Do I feel happy about it or not? And kind of going back and being like, did I get this right with my own thinking, like as part of academia?

So I'm so happy that I'm part of those spaces, and also just realizing how much work goes into not only on the side of these commissions and these councils that are part of, but also on how much unpaid labor goes into the advocacy, and how much I appreciate all the people that are part of these processes to really get their voices heard and really address things that are important to them in their communities.

Anne Meeker: Definitely. And this is something that came up in one of our recent conversations for this newsletter, with the Convention of States folks who mentioned, "Hey, most of us who can afford to go to Columbus and go to the State House are retired." So just the amount of advocacy that relies on retired folks and folks who aren't working for other reasons, like you said, a high school student holding a cell phone is incredible.

And one thing that you really touch on in the toolkit is when is it appropriate and why is it important to think about compensating people for being engaged? And just as a former staffer, my hackles immediately go up thinking about paying people to go to a town hall. Like, that's where we get a lot of conspiracy theories about paid actors. But I see the point about, “Hey, this is labor.” So can you walk me through just where you think it should make sense to pay people for this?

Sam McDonald: Yeah. No, that's a great question. And you definitely have to tread lightly with a lot of those assumptions, especially with town halls. But, when it comes to the situation of compensation, oftentimes Members of Congress and other public officials, they always wait for the constituent to reach out to them. But if there were avenues that would allow those officials to reach out to the people and say, "Hey, I have a question I want to engage in, like a deep conversation about this and get perspectives from lots of different people with lots of different backgrounds,” that requires a lot of coordination, but also recognizing the fact that that's either asking people to do this voluntarily, or we're going to have to pay them for their time. And there's lots of amazing examples, like the Irish citizens assemblies and all the different other citizens assemblies across the globe, where they recognize that if we're going to ask people to be part of something, they should be compensated in some way for their time. It doesn't necessarily mean it has to be financial.

I mean, we do have jury duty as a requirement that's just part of being a citizen — but with a Member of Congress, it's people taking time out of their day voluntarily. So are there avenues that say, "Hey, you know, you show up to this event for like a few hours, you engage really meaningfully, like we'll compensate you in some way for that time. We want to hear from you." And there is some evidence. I mean, there's evidence you can find a little bit on both sides, but there is some evidence that I've seen that sort of gears towards — when you compensate people for their time, they actually engage more meaningfully in whatever situation is happening.

So I think there's a lot of opportunity for that, especially when it comes to Members of Congress. If we're going to have this more deep, long engagement that can lead to something more successful, it's going to take a lot of work from lots of different people, and some of that may need to be compensated somewhat.

Anne Meeker: Interesting. And obviously that would take a lot of infrastructure changes with giving people the resources to pay people — like that wouldn't be a cheap undertaking, especially in a resource-starved institution like Congress. But yeah, it's kind of the old thing that I tell people who ask me, “should I write my Member of Congress? How should I do it?” You're going to get out what you put in. This is the same for the institution as well.

Sam McDonald: Yeah. No, absolutely.

Anne Meeker: Awesome. Sam McDonald, thank you again so much for taking the time for all of your work on this. Again, it has been so foundational to the work that we've continued to do for POPVOX Foundation. So I am delighted that we got the chance to catch up. And I know this isn't the last we'll see of you here.

Sam McDonald: Awesome. Well, thank you so much. I really appreciate chatting.

Especially following the passage of the Government Service Delivery Improvement Act in early 2025: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/house-bill/5887

Before anyone brings up USPS vs. UPS/FedEx…I hear you. But for most programs, the government is the only game in town.

The more I thought about it, the more I disagreed with the notion that Federal services should not be thought of like customer service, since constituents have more control and say over the agencies. Where I disagree is that it may be true of local or perhaps state government, much less so at the federal level. I have watched for years on CSPAN as Congress has tried to hold federal bureaucrats accountable. If Congress can not hold officials accountable, how would we, the people?